Folks who desire to pursue sustainable lifestyles quickly discover a need to become semi-competent on a vast variety of many basic skills. Sustainable lifestyles require the courage to dive in and try new things, the creativity to be innovative, and a desire to gain the satisfaction that can only be achieved by building and doing things with one’s own hands. Living sustainably requires sweat equity, physical productivity, a willingness to be intellectually stretched, and maybe most importantly, the acceptance of non-perfectionism. I for one am a Jack of all trades, but clearly not a master of any.

Having lived the majority of our married life an hour from the city has forced me and Nancy to build and fix things without the luxury of hired expertise. Not only is it expensive to get professionals to drive this far every time something goes wrong, but it’s been our experience that most things of importance decide to break in the night, during holidays or heavy snow storms. Our choice of lifestyle has motivated us to develop the basic skills of welding, household electrical, plumbing, carpentry, cabinetry, shade-tree mechanics, food preservation (like canning, freezing and drying) as well as a plethora of other things simply for survival sake. Along the way I’ve learned to work with leather using rivets and awls in order to repair broken harness and saddles, while Nancy learned to sew ( originally on a treadle machine). Together we’ve learned to do emergency veterinary work, agriculture projects of all kinds, install irrigation systems, build fence lines, perform masonry work and pour concrete. We do none of these things well enough to make a living at them, but find great pleasure accomplishing and creating things with our own hands. The money we have saved by doing things ourselves has provided thousands of dollars which has enabled us to invest in other new projects.

Being a do-it-yourselfer requires two essentials: the attainment of some basic tools and capable people who can teach you how to use them. Now that I’m in my 60s I have an adequate work shop, but for years Nancy and I didn’t have the available resources to purchase decent tools. In the early days of our marriage when we lived off the grid, we learned to do most everything with what now might be considered archaic hand tools. Most of those tools were hand-me-downs from my father and Great Uncle Floyd, who not only gave me tools but also taught me how to use them. In retrospect, the apprenticeship I received from them was invaluable for our life today. I learned the basics of building construction while spending endless weekends working on our old family ranch together. I’ll never forget how Uncle Floyd, being too old to climb up tall ladders or straddle beams, would instruct my dad and I as we teetered on ceiling rafters above him. Every 2×4 had to be cut perfectly square with the hand saws that he had skillfully sharpened for us. Every board had to be accurately measured and hand nailed into its proper place. For Uncle Floyd, carpentry was an art form – a value he joyfully passed on.

I think teaching us somehow gave his life more value knowing that the skills he had attained were appreciated and wanted and wouldn’t end with him. I never owned a Skill saw or an electric drill motor until I was nearly thirty years old and still cherish the handmade wood plane and other tools Uncle Floyd gave me before he died in the 70s. The work we accomplished over the course of a long hard day then could later be done in a matter of hours with the aid of modern tools, but the satisfaction of a job well done somehow was more rewarding because of the labor intensive work it required. There was something very special about being a young boy included in men’s work, something that is being tragically lost with the epidemic of broken families and absentee fatherhood. I took those special times for granted then, but now realize what an advantage they gave me later in life. Even some of the rock walls I’ve built here at Timber Butte have my dad’s fingerprints on them as he occasionally still drops by and lends a helping hand at age 91.

I took the skills my dad and uncle gave me and later supplemented them by reading “how-to” books and inquired of people who knew things I was yet eager to learn. My long-time friend Paul Taylor spent many days teaching me how to weld as we constructed a steel flatbed trailer together. That was over 30 years ago and the old trailer is still functional, moving hay from our field to this day.

I learned to electrically wire a house from another friend and basic plumbing again from my dad. In the early days we used all galvanized steel pipe, custom cutting and threading each piece with an old die set that I still occasionally resort to when not using newer plumbing products. Building materials are constantly changing and improving, which keeps all of us want-to-be handy men on our toes, forcing us to keep our apprentice hats on for life.

Society has changed since I was a young man and in many ways, not for the better. Because of these changes opportunities to grow in these basic skills are sadly being lost. In my earlier days apprenticeship wasn’t thought of as a deliberate training process, but was rather naturally rooted out of necessity and sometimes even survival.

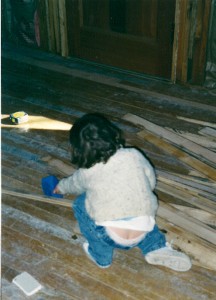

A few years ago, realizing the value of families working together Nancy and I decided to buy a small piece of wilderness land and invite our kids to join us in building a family cabin together. The project took us nearly five years and in fact still goes on to this day. (See entry 123 & 117) At one point we had four generations of the Robinson family working together as my dad built his famous rock walls and my granddaughter entertained her mother and uncle while they worked together.

Apprenticeship was meant to be a generational matter in families, communities and churches. One of the greatest examples I know of is found in the Gospels as Joseph apprenticed his son Jesus in the skills he knew (he too was a carpenter) and how Jesus then took the value of apprenticeship and in turn made disciples of those that desired to carry on his teaching and legacy. Apprenticeship has always been God’s idea but is rapidly being lost in today’s godless culture. If we are to live more sustainable lives we must turn back to this basic biblical value once again so that our next generation may have something of value to gain and to pass on. It is a matter of survival.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.